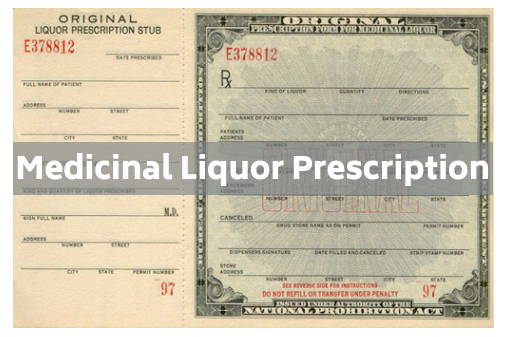

We can’t say that medicinal liquor of the early 20th century in the United States foretold the path of today’s medical cannabis, but with the medical cannabis / cannabis licensing and permitting explosion and backlog some interesting comparisons can be made. Let’s take a look at medicinal liquor’s history in Washington state.

We can’t say that medicinal liquor of the early 20th century in the United States foretold the path of today’s medical cannabis, but with the medical cannabis / cannabis licensing and permitting explosion and backlog some interesting comparisons can be made. Let’s take a look at medicinal liquor’s history in Washington state.

Prohibition on liquor in Washington State went into effect on January 1, 1916 several years in advance of the 1920 passage and national implementation of the 18th amendment. For a time, medicinal liquor, sold at permitted drug stores, in the state was still available. It is said that in the subsequent three months of that law’s passage in Seattle alone, 65 new drugstores opened to sell medicinal liquor. This was short lived and came to an end with the introduction in Washington Sate of the “bone dry” law passed in February 1917. The law allowed permitted drugstores to continue to sell medicinal liquor but prohibited the importation of medicinal liquor into Washington state where, as it happens, liquor was not being produced. Further compounding this dilemma, federal legislation known as the Reed-Randall Bone Dry Act passed by congress outlawed the shipping of liquor into states that had dry laws.

Medicinal Liquor and a Change of Heart

By 1932 there began in the country a change of heart about prohibition and with this sentiment, previously placed restrictions began to disintegrate. Washington state voters passed in November 1932 Initiative 61 repealing the state’s bone-dry law. Though the national prohibition was still in effect, repeal of the bone-dry law along with prohibition’s allowance for medicinal liquor paved the way for the reintroduction of medicinal liquor in Washington state. Many of the state’s citizens then began to get sick and were in need of their medicine. Initially there were some restrictions in place such as only one pint every 10 days could be prescribed to a patient, but people were asking for their medicine!

Quote from an article on medicinal liquor in Washington state written by Phil Dougherty.

“The repeal of the city’s dry ordinance was scheduled to become effective on December 29 1932. But when the big day arrived, there was a problem. The booze was in town, but almost no one could get it in a Seattle drugstore. The problem was with the permits that doctors and druggists were required to have in order to prescribe and sell liquor. They had inundated the Bureau of Industrial Alcohol with so many applications that the bureau was overwhelmed and hadn’t approved most of them. Moreover, many doctors hadn’t filled out the required questionnaire that accompanied the permit application. Roy C. Lyle, the bureau’s supervisor, explained impatiently:

“I’m signing them [permits] as fast as I can. But there is still a great deal of investigational work to be done. Of course, the importance of this medicinal liquor is being exaggerated. It is sold for medicinal purposes only and is not intended for beverage purposes. It can only be sold on doctor’s prescription and is not supposed to be authorized by a doctor except for the use of a really sick patient”

Once these flood gates opened, congress removed restrictions on how much medicinal liquor a doctor could prescribe and eventually in 1933 prohibition was lifted.

Connect